What Major Changes Do Non For Profit Hospitals Face In 2018

Abstract

Groundwork

Hospitals face financial pressure from decreased margins from Medicare and Medicaid and lower reimbursement from consolidating insurers.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to determine whether hospitals that became more than profitable increased revenues or decreased costs more and to examine characteristics associated with improved financial performance over time.

Design

The blueprint of this study is retrospective analyses of U.S. non-federal acute care hospitals between 2003 and 2013.

Subjects

At that place are 2824 hospitals as subjects of this study.

Main measures

The main measures of this study are the change in clinical operating margin, change in revenues per bed, and change in expenses per bed between 2003 and 2013.

Key results

Hospitals that became more than profitable had a larger magnitude of increases in revenue per bed (well-nigh $113,000 per year [95% confidence interval: $93,132 to $133,401]) than of decreases in costs per bed (about − $ten,000 per year [95% confidence interval: − $28,956 to $9617]), largely driven by college non-Medicare reimbursement. Hospitals that improved their margins were larger or joined a hospital system. Not-for-turn a profit status was associated with increases in operating margin, while rural status and having a larger share of Medicare patients were associated with decreases in operating margin. There was no association betwixt improved infirmary profitability and changes in diagnosis related group weight, in number of profitable services, or in payer mix. Hospitals that became more than profitable were more likely to increase their admissions per bed per year.

Conclusions

Differential price increases have led to improved margins for some hospitals over time. Where significant price increases are not possible, hospitals will have to become more than efficient to maintain profitability.

INTRODUCTION

U.S. hospitals continue to face up significant financial force per unit area. Consolidation of health insurers has put force per unit area on commercial prices.1,2 Medicare margins remain negative,three and Medicaid margins have fallen essentially.4 A recent paper suggests that the share of hospitals with negative margins could rising from i-quarter to 41% in a decade.5 Despite these challenges, boilerplate hospital margins have remained steady, and at many institutions they have increased. The average hospital'south full operating margin rose from four.3% in 2007, the year before the Great Recession, to about vi.2% in 2014.3

How do hospitals deal with such fiscal pressures, and, in some cases, thrive? The literature suggests several strategies hospitals have used in the by. Some strategies may increase revenues. One such strategy is to utilise bookkeeping changes; for case, hospitals might "upcode" a patient into a more than severe, and thus more reimbursed, diagnosis related group (DRG).6,7 Upcoding was relatively common in the 1990s, but bear witness suggests that upcoding is less prevalent now, likely due to increased authorities focus.vi A second such strategy is to provide more profitable services.8,9 Technologically-intensive services are reimbursed amend, and hospitals historically take been posited to adopt engineering to heighten acquirement.10 Hospitals accept continued to acquire well-reimbursed technologies in contempo years,11,12 though these are moving to the outpatient setting. Third, hospitals can change the mix of patients served, away from less-reimbursed public insurance enrollees towards ameliorate-reimbursed privately insured patients.xiii,fourteen,–15 A 4th acquirement-raising strategy is to enhance prices. Infirmary consolidation has increased markedly, and a rich literature links greater concentration with higher prices.16,17,–eighteen Having greater prestige may too allow a hospital to negotiate higher prices.19 Other strategies may decrease costs. One such strategy is reducing length of stay. Such reductions were prominent in the 1980s and 1990s when many payers switched to prospective payment systems for inpatient intendance, but further reductions may exist difficult.20

In this report, we apply national data to answer three questions. First, how has variation in hospital operating margins changed over time? Second, what are the characteristics of hospitals that increased their operating margin over fourth dimension? Third, what financial and clinical steps did hospitals take to become profitable?

METHODS

Data

Nosotros used data from the Medicare Cost Reports from 2003 to 2013, part of the Healthcare Cost Report Data Organisation (HCRIS). The HCRIS data have been used by the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) and others to calculate hospital margins.three,21 We linked HCRIS data to the American Hospital Association (AHA) annual survey, which provides information on hospital characteristics such equally teaching status, and the Eye for Medicare and Medicaid Services Impact Files, which provide hospital case-mix information. For a subset of analyses examining length of stay and DRG weight, HCRIS data were also linked to the Healthcare Price and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID); all other analyses used our full sample. The states for which SID information were available to us for the examined fourth dimension period were Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Washington.

Written report Population

Our sample included 2824 hospitals that met the following conditions: they existed in the AHA data from 2003 to 2013; they were hospitals serving medical and surgical patients or were hospitals specializing in cancer, cardiac, or orthopedic intendance; they were non federal regime hospitals; they were not critical access hospitals; and they submitted HCRIS information from 2003 to 2013. Analyses using the SID information included 587 of the above 2824 hospitals.

Study Design, Variables, and Statistical Analyses

Our primary measure of functioning was clinical operating margin, divers as cyberspace patient revenues minus total operating expenses (e.g., staffing costs, medications) divided past net patient revenue. This mensurate excludes non-clinical sources of acquirement such every bit donations and investment income.22 While MedPAC uses a total operating margin measure that includes these other sources of revenue, our focus on clinical operations led us to remove them. These margin measures are highly correlated. In 2013, the correlation of clinical operating margin with total operating margin was 0.77, and the correlation of the difference betwixt 2003 and 2013 in clinical operating margin with the difference in total operating margin was 0.78.

We dropped values of operating margin in 2003 or 2013 that were greater than 50% or less than − l% (111 hospitals affected) as these were likely due to reporting errors, replacing missing values with the adjacent twelvemonth (i.e., 2004 or 2012) when possible (63 hospitals affected).

To address our first question, variation in margins over time, we examined the distribution of margins in 2003 and in 2013. We too examined the percent of hospitals that were in a particular operating margin category in 2003 that remained in that aforementioned category in 2013 and the per centum that moved to a higher or lower margin category.

Nosotros then calculated overall net patient revenues per bed and overall costs per bed as well as Medicare and non-Medicare (private, Medicaid, and uninsured) revenues per bed. We estimated multivariate linear regressions relating these financial variables (our chief outcomes) to our principal contained variable, which was a categorical variable that took the value of 1 for hospitals in the upper quartile of change in operating margin betwixt 2003 and 2013, − 1 for hospitals in the lower quartile of change in operating margin, and 0 for hospitals with a change in operating margin in the middle two quartiles. This categorical variable simulates the alter in going from the lowest quartile of alter in operating margin (hateful change of − 19.i%) to the middle two quartiles (mean modify of − 1.6%) or from the middle 2 quartiles to the highest quartile (mean alter of 12.8%), allowing us to ask whether moving to a higher category of change in operating margin was associated with higher revenues, lower costs, or both. Other hospital characteristics we command for include beingness a large hospital (> 300 beds), turn a profit and ownership status, rural location, teaching status, percent of admissions from Medicare, percentage of admissions from Medicaid, being a specialty hospital, instance mix, and country, all of which were measured in 2003.

To address our second question about which hospitals had better financial performance changes, nosotros ran multivariate linear regressions in which our main outcomes were one) a continuous measure out of change in operating margin betwixt 2003 and 2013, and two) changes between 2003 and 2013 in non-Medicare revenue per bed and in expenses per bed, and our independent variables of interest were hospital characteristics. We focused on two categories of hospital characteristics: infirmary prestige and hospital concentration. We defined prestigious hospitals as (1) a teaching hospital (defined as a member of Council of Teaching Hospitals); and (2) a U.South. News and World Reports top hospital in 2003, separated into (a) U.Southward. News "Honor Whorl" hospitals, (b) U.South. News Best Hospitals for cancer, heart and heart surgery, or orthopedics that were not also "Honor Gyre" hospitals, and (c) all other hospitals ranked in U.S. News that yr. Nosotros used two measures for hospital concentration: (one) whether a hospital that was not part of a hospital system in 2003 joined a system prior to 2013 and (2) a hospital's or its hospital organization'due south share of beds in its hospital referral region (HRR) in 2003. Nosotros regressed the principal outcomes in a higher place on these measures of infirmary prestige and hospital concentration in one regression, controlling for other hospital characteristics noted above.

For our third question—changes in hospital clinical characteristics associated with operating margin increases—our main outcomes of involvement were (ane) changes in boilerplate DRG weight; (ii) changes in the number of profitable services or technology; (3) changes in hospital capacity utilization and length of stay; and (four) changes in payer mix. In separate regressions, we regressed these chief outcomes on our categorical variable of quartile of change in operating margin, decision-making for other hospital characteristics noted above. For DRG weight, nosotros used the SID data to calculate the difference in the boilerplate DRG weight of an admission between 2003 and 2013. For profitable services or applied science, we identified xiv services or technologies present in the AHA information betwixt 2003 and 2013 that accept been previously identified in the literature every bit profitable23 and calculated the difference in number of these services or technologies betwixt 2003 and 2013. Nosotros measured infirmary capacity utilization as the average number of admissions per bed per year. For length of stay, we used the SID data to calculate the divergence in average length of stay between 2003 and 2013. For payer mix, we used AHA data to calculate the difference in percent of admissions that were from Medicare, Medicaid, and other sources (private and uninsured) between 2003 and 2013.

Values were normalized to 2013 dollars using the consumer price alphabetize. Analyses were conducted using Stata fifteen.0 and used robust standard errors. Report blessing was obtained from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

RESULTS

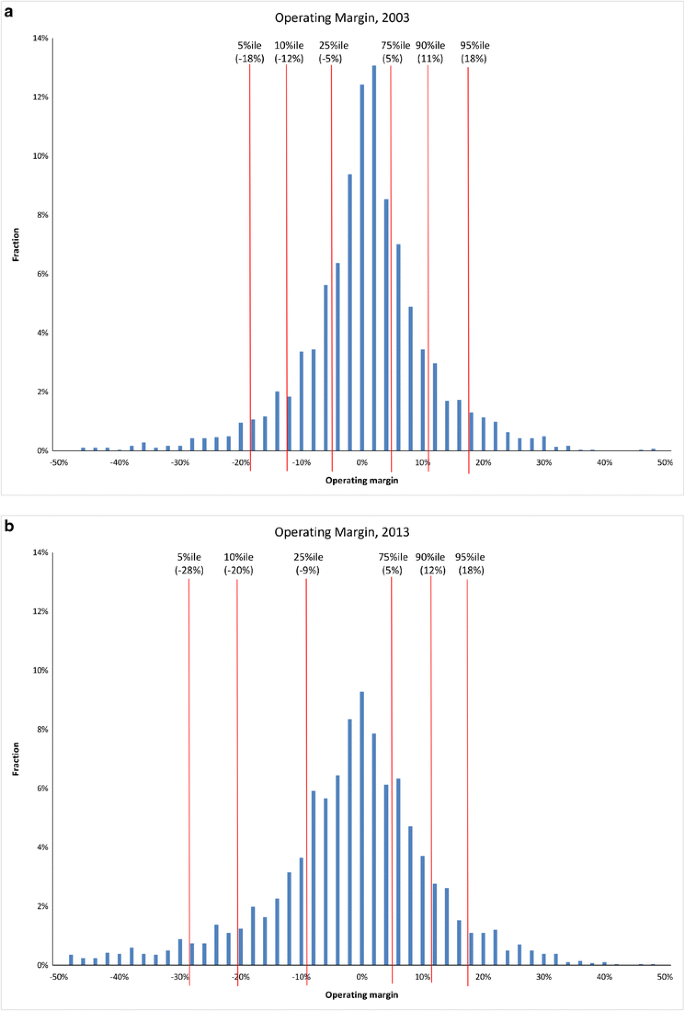

In 2013, the boilerplate hospital had a clinical operating margin of − 2.seven%. By comparison, total operating margin that year in our sample averaged five.0%. (This differs from the margin reported by MedPAC because we examine a different gear up of hospitals.) The distribution of clinical operating margins in 2003 and in 2013 is shown in Figure 1. The standard deviation of margins was significantly college in 2013 (xiii.6%) than in 2003 (x.six%) (p value for departure < 0.001). 1 quarter of hospitals in 2013 had margins of more than 5%, and the top five% of hospitals had margins of more than eighteen%. The boilerplate hospital had a subtract in margin of − two.4% between 2003 and 2013.

Distribution of operating margin in 2003 and in 2013. Source: Authors' analysis of Healthcare Cost Written report Information Organization data

Almost hospitals did non movement far in the operating margin distribution. The correlation between operating margin in 2003 and operating margin in 2013 was 0.44. For those in the lowest quartile of operating margin in 2003, 43% stayed in the lowest quartile in 2013; most of the rest moved to the centre quartiles. Similarly, 49% of hospitals in the highest quartile in 2003 remained in that quartile in 2013 (online Appendix Table 1).

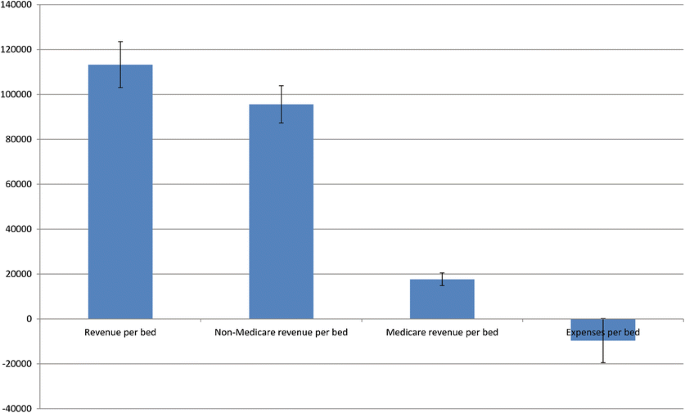

We found that moving to a higher category of modify in operating margin was associated with increases in revenues per bed, not with decreases in costs per bed (Fig. 2). Moving from a lower category of alter in operating margin to a college ane was associated with an increase in revenues per bed of almost $113,000 per yr (95% confidence interval [CI]: $93,132 to $133,401). About of this revenue increase came from not-Medicare payers. Non-Medicare revenue rose by near $96,000 per bed (95% CI: $79,348 to $111,867); Medicare revenue increases were nearly one-fifth as big. Moving to a higher category of change in operating margin was associated with decreases in expenses per bed of about − $10,000 that did not reach statistical significance (95% CI: − $28,956 to $9617).

Changes in revenues and expenses per bed for hospitals with increases in operating margin betwixt 2003 and 2013. Source: Authors' analyses of Healthcare Toll Report Information System data, American Infirmary Association (AHA) annual surveys, and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Impact Files. Notes: Each bar represents a separate multivariate linear regression in which "Change in Operating Margin Category" is the main independent variable. "Modify in Operating Margin Category" is an indicator variable that takes the value of 1 for hospitals with a change in operating margin in the highest quartile, −1 for hospitals with a change in operating margin in the lowest quartile, and 0 for hospitals in the middle quartiles. Models arrange for hospital size (a binary variable for hospitals with greater than 300 beds) in 2003, profit and buying status in 2003, location (urban versus rural), pedagogy status (member of Quango of Didactics Hospitals) in 2003, per centum admissions from Medicare in 2003, percent admissions from Medicaid in 2003, specialty (cancer, cardiac, or orthopedic) infirmary in 2003, case-mix index in 2003, and country. Values were normalized to 2013 dollars using the consumer price index. Error bars stand for standard errors

Characteristics of Hospitals that Improved Their Operating Margin

Table 1 shows hospital characteristics in 2003 and how these vary across categories of changes in operating margin. The boilerplate hospital has 225 beds. Rural hospitals equanimous 10% of the sample. Medicare made up 45% of admissions and Medicaid made upward 17%.

Rural hospitals were less likely to be in the highest quartile of changes in operating margin compared to the lowest quartile. In that location was a slightly college percentage of publicly insured patients (Medicare and Medicaid) in hospitals in the everyman quartile of changes in operating margin compared to the highest quartile. Teaching hospitals were more likely to exist in the highest quartile than the lowest quartile. Hospitals that scored higher on U.S. News for cancer, middle and middle surgery, or orthopedics were more probable to be in the highest quartile than the lowest quartile. Hospitals or their affiliated infirmary systems with a larger share of beds in its region in 2003 were more probable to be in the highest quartile than the everyman quartile.

Table ii shows regression results of infirmary characteristics associated with margin increases. The dependent variable in the offset cavalcade is continuous change in operating margin between 2003 and 2013. Being an "Honor Roll" hospital was associated with operating margin decreases (− 0.061 [p = 0.004]). Joining a infirmary organisation (0.018 [p = 0.01]) and having a larger share of beds in 1's HRR (0.079 [p < 0.001]) were associated with operating margin increases. Not-for-profit status was associated with operating margin increases, while rural condition was associated with operating margin declines. Hospitals with a high percent of Medicare patients were more likely to have margin declines.

The second and 3rd columns of Table 2 examine how these hospital characteristics are associated with changes in not-Medicare revenue per bed and expenses per bed. Non-Medicare revenues per bed increased significantly in didactics hospitals, hospitals on the U.S. News "Honor Curl," and hospitals noted for cancer, heart and centre surgery, or orthopedics. Meanwhile, being a didactics hospital and an "Honor Roll" hospital were associated with large increases in expenses per bed, while for-profit condition was associated with big decreases in expenses per bed.

Clinical Changes

When testing hypotheses regarding what hospitals may have done to increase their operating margins (Table 3), moving to a higher category of change in operating margin was non associated with increases in DRG weight or number of profitable services. In that location were too no significant changes in payer mix associated with moving to a higher category of alter in operating margin. In that location was an association between moving to a college category and decreased length of stay that approached statistical significance (− 0.070 [p = 0.057]). Hospitals that moved to a college category were more likely to increase their admissions per bed per year (2.41 [p < 0.001]). This increment is v% of the average number of admissions per bed in 2003, while non-Medicare revenues per bed increased 55% for the top quartile hospitals.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the financial situation of hospitals is critical at a fourth dimension of major wellness system change. Several studies evidence the harmful effects that reimbursement pressure tin can cause; financial pressure level has been associated with lower process quality and with closure.24,25,26,27,–28 Inquiry on successful survival has not been equally well-explored. In this paper, we consider characteristics of hospitals that take done well and investigate what actions hospitals have taken to improve their fiscal functioning.

Nosotros reach several key findings. Beginning, there is wide variation in operating margin over time. The distribution of operating margins has go more than dispersed in the past decade. Thus, focusing only on the average hospital misses a good deal of variation.

Second, hospitals that became more profitable primarily did so by increasing the revenue they took in, especially from non-Medicare (likely private) payers, non by cut expenses. College revenue can come from higher prices or from greater volume of services. Hospitals with increases in operating margin had modest increases in admissions per bed and small-scale decreases in length of stay, but at that place was no clan with increases in DRG weight. Results were broadly similar when using admissions as a denominator (online Appendix Tables 2 and 3). Like acquirement per bed, revenue per admission for the superlative quartile hospitals also rose by much more than admissions per bed. We constitute very few differences between hospitals with increases in profitability and those without such increases in availability of assisting services and technology. Our data do non provide firm bear witness on the use of such technology, but we suspect that technology utilise is not a major driver. Almost lxxx% of the increment in revenue for hospitals with large margin increases comes from non-Medicare payers. Yet Medicare accounts for one-half of all infirmary admissions and a quarter of all outpatient visits,29 so we do not think that increases in procedure use that led to such revenue increases would be and then concentrated in the non-Medicare population.

Selden et al. recently documented widening departure betwixt individual and public (Medicare and Medicaid) payment rates for inpatient hospital stays since 2001.xxx Our findings suggest that this divergence may be due to hospitals raising prices on private insurers. Further evidence in support of this comes from the variables measuring prestige and consolidation. Teaching hospitals, U.S. News "Honor Coil" hospitals, and those hospitals recognized past U.S. News as being proficient in cancer, cardiology, or orthopedics had large increases in non-Medicare revenue. Many of them also had large increases in expenses (peculiarly Honor Roll hospitals), so that overall operating margins remained modest. While we do not mensurate prices direct, other testify suggests that these institutions may have raised prices. For example, recent reports suggest that the prices paid by insurers to hospitals in Massachusetts,31 and in the Usa more more often than not,32 are unrelated to quality of care just correlated with the hospital'southward market place position. Similarly, studies have establish that hospitals that merge accept large increases in their price.16,33

Our study has several limitations. The data on hospital costs come from cocky-reports. While they are widely used past groups such equally MedPAC, the data are not uniformly audited. Further, debt payments may be included at the hospital level for some institutions just taken out of the hospital level (and recorded at the system level) for others. For some of our conclusions, causality is unknown. For case, hospitals that join a system may have bought other hospitals or been caused because they were assisting, leading to an association between consolidation and margins that is a outcome of contrary causality. Collections may accept improved in hospitals whose operating margins increased, but we are unable to mensurate this. Analyses on DRG and length of stay used a smaller sample of states and hospitals; there may have been significant associations if a larger sample had been used. Finally, nosotros could not carve up out Medicaid revenues from other non-Medicare revenues.

In sum, our enquiry suggests that differential price increases may contribute to the growing difference of hospital margins in the past decade. While this explanation may explicate the recent period, information technology may be more difficult to command higher prices in the futurity, as the increasing prevalence of patient toll sharing and a move towards more restrictive payments by insurers may constrain what even the most prestigious hospitals can charge. For hospitals to stay profitable, they may have to do what few take washed to date–control their costs.

References

-

Melnick GA, Shen Y, Wu VY. The increased concentration of health plan markets can benefit consumers through lower infirmary prices. Health Aff 2011; 30: 1728–33.

-

Moriya As, Vogt WB, Gaynor M. Hospital prices and market structure in the hospital and insurance industries. Health Econ Policy Law 2010; five: 459–79.

-

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. 2016. Available at: http://world wide web.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/march-2016-written report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf. Accessed Jan iv, 2018.

-

American Infirmary Association. Fact sheet: the magnitude of the cuts hospitals already are absorbing. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/12/12factsheet-absorbingcuts.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

-

Hayford T, Nelson L, Diorio A. Projecting hospitals' profit margins under several illustrative scenarios. Available at: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/workingpaper/51919-Hospital-Margins_WP.pdf. Accessed January four, 2018.

-

Dafny L. How to hospitals respond to cost changes? Am Econ Rev 2005; 95: 1525–47.

-

Silverman East, Skinner J. Medicare upcoding and hospital ownership. J Health Econ 2004; 23: 369–89.

-

Chandra A, Skinner J. Applied science growth and expenditure growth in health care. J Econ Lit 2012; fifty: 645–80.

-

Newhouse JP. Medical intendance costs: how much welfare loss? J Econ Perspect. 1992; 6: 3–21.

-

Bates LJ, Mukherjee K, Santerrre RE. Market place structure and technical efficiency in the hospital services industry: a DEA arroyo. Med Intendance Res Rev. 2006; 63: 499–524.

-

Carrier ER, Dowling M, Berenson RA. Hospitals' geographic expansion in quest of well-insured patients: will the issue be amend intendance, more cost, or both? Health Aff 2012; 31: 827–35.

-

Devers KJ, Brewster LR, Casalino LP. Changes in hospital competitive strategy: a new medical arms race? Health Serv Res 2003; 38: 447–69.

-

Bazzoli GJ, Clement JP. The experiences of Massachusetts hospitals equally statewide health insurance reform was implemented. J Health Intendance Poor Underserved 2014; 25: 63–78.

-

Dranove D, White WD. Medicaid-dependent hospitals and their patients: how accept they fared? Health Serv Res 1998; 33: 163–185.

-

Friedman B, Sood N, Engstrom K, McKenzie D. New testify on infirmary profitability by payer grouping and the furnishings of payer generosity. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2004; 3: 231–46.

-

Gaynor Thousand. Health care industry consolidation [argument before the Committee on Means and Means Wellness Subcommittee, U.s. Hours of Representatives]. Available at: http://waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/Gaynor_Testimony_9-ix-11_Final.pdf. Accessed January iv, 2018.

-

Dafny, L. Estimation and identification of merger effects: an application to hospital mergers. J Police Econ 2009; 52: 523–50.

-

Cutler DM, Scott Morton F. Hospitals, market place share, and consolidation. JAMA 2013; 310: 1964–70.

-

Bai Yard, Anderson GF. A more than detailed agreement of factors associated with infirmary profitability. Wellness Aff 2016; 35: 889–897.

-

Schwartz WB, Mendelson DN. Hospital cost containment in the 1980s—hard lessons learned and prospects for the 1990s. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1037–42.

-

Volpp KG, Konetzka RT, Zhu J, et al. Effect of cuts in Medicare reimbursement on process and issue of care for acute myocardial infarction patients. Apportionment 2005; 112: 2268–75.

-

Pink GH, Howard A, Holmes GM, et al. Differences in measurement of operating margin. Available at: http://www.flexmonitoring.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BriefingPaper17_OperatingMargin.pdf. Accessed January iv, 2018.

-

Horwitz JR, Nichols A. Hospital ownership and medical services: market mix, spillover effects, and nonprofit objectives. J Health Econ 2009; 28: 924–37.

-

Ly DP, Jha AK, Epstein AM. The association between infirmary margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26: 1291–half-dozen.

-

Bazzoli GJ, Chen HF, Zhao M, et al. Hospital financial condition and the quality of patient intendance. Health Econ 2008; 17: 977–95.

-

Encinosa Nosotros, Bernard DM. Hospital finances and patient safe outcomes. Inquiry. 2005; 42 : lx–72.

-

Williams D, Hadley J, Pettengill J. Profits, community role, and infirmary closure: an urban and rural analysis. Med Care 1992; 30: 174–87.

-

Duffy SQ, Friedman B. Hospitals with chronic financial losses: what came next? Wellness Aff 1993; 12: 151–63.

-

Centre for Disease Command and Prevention. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 summary tables. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2010_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed January iv, 2018.

-

Selden TM. Karaca Z, Keenan P, White C, Kronick R. The growing deviation between public and private payment rates for inpatient hospital intendance. Health Aff 2015; 34: 2147–50.

-

Office of Attorney General Martha Coakley. Examination of health care price trends and toll drivers. Available at: http://world wide web.mass.gov/ago/docs/healthcare/2010-hcctd-total.pdf. Accessed January iv, 2018.

-

Cooper Z, Craig SV, Gaynor G, Reenen JV. The price ain't correct? Hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured. NBER working paper no. 21815. Bachelor at: http://world wide web.nber.org/papers/w21815. Accessed January four, 2018.

-

Gaynor G, Town R. The impact of hospital consolidation—update. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf73261. Accessed January four, 2018.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number U19HS024072 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, by grant number R37AG047312 from the National Institute on Aging, and by grant number T32AG000186 from the National Constitute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does non necessarily stand for the official views of the Bureau for Healthcare Enquiry and Quality or the National Found on Aging.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do non take a conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Ly, D.P., Cutler, D.M. Factors of U.S. Hospitals Associated with Improved Profit Margins: An Observational Report. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1020–1027 (2018). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11606-018-4347-four

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Outcome Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1007/s11606-018-4347-4

KEY WORDS

- profitability

- prestige

- market power

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-018-4347-4

Posted by: schneiderbetmadvand.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Major Changes Do Non For Profit Hospitals Face In 2018"

Post a Comment